Strange Coincidences, Random Findings and Opportune Synchronicities Surrounding the Making of the J.K. Rowling Braille Artist’s Book

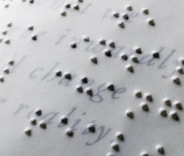

Ultimately it was my preschool son who supplied the answer. I sat absorbed at the old wooden kitchen table, doodling in my sketch pad and staring out at the garden as my son finished his after-school snack. “Mommy, look what I did today!” he announced, demanding my attention. He pulled from his overstuffed backpack some dirty clothes, a half-eaten bagel, several picture books and a crumpled white paper. He grinned proudly as he waved it aloft, “My name in braille!”

There, smudged in peanut butter and offered by a grinning boy, was my answer.

THE NEXT CHALLENGE – how best to begin learning braille. My son again provided the solution. As I dropped him off at his nanny’s, he reported that Mom was using “his braille” in a book. “Oh, how exciting,” Irene exclaimed. “Did you know I used to teach braille? Stay for a moment while I get a few things from my basement.” Though we’d known Irene for years, this braille expertise was news to me. She soon emerged with a dusty box, untouched for the past 10 years: all the brailling tools, introductory books, examples, and teaching tools I could want. Staggeringly good luck – all offered to me in a neighboring town on the rural peninsula we call home.

As I continued envisioning the book, I focused upon Rowling’s chosen quote from the Greek philosopher Plutarch: “What we achieve inwardly will change outer reality.” Indeed, it was almost as if when I knew inwardly what I needed to achieve to take the next step in the project, the solution would magically appear.

That weekend my husband and I went to pick up our new baby lambs about 45 minutes down the Cape. We stop by this farm once or twice a year as we’ve become friends with the farmers, though it is not on our normal route to or from anywhere else. As we neared the farm my husband noticed a small sign in a nondescript plaza: Bookbinding Services. We stopped, entering what appeared to be another era.

Talin Bookbindery is a small shop run by a brother and sister. Their tools, materials and methods of construction are the same ones that have been employed by bookbinders for centuries. Had the shop not had electric lights, I could easily have believed I’d stepped into the 1800s. The moment I walked through the door I knew I had found exactly what I had been looking for; Jim Talin’s patience and expertise surpassed my already high expectations. The quality of workmanship, attention to detail, ability to think outside of the (literal) box, and love of literature and old books were immediate shared passions.

“WHY BRAILLE?” I found myself asking again. Yes, braille is a powerful visual metaphor to parallel failure (most of us can’t read braille) and to spark the imagination (is the book’s translucent overlay a code?). Furthermore, braille as a cipher was ideal for a Rowling speech given her famous subject matter. Yet, “Who was Louis Braille?” was a question I needed to answer.

If you’ve linked to my Note on the Design from the book, you now know the young Louis Braille’s story. When I first discovered it, I sat alone in my studio staring at the goosebumps tingling my arms. I couldn’t wait to tell my own young boy.

© P.F. Randolph, 2010. All rights reserved.

Furthermore, though advances in technology can now translate spoken words to text and vice versa, auditory technologies cannot supplant reading and writing. We would not suggest that our sighted children forgo learning the alphabet, and instead teach solely through film, computer and radio. As an artist I can’t imagine not being able to put my thoughts onto paper. A concrete, tactile representation of my thinking is fundamental to my understanding of the world around me.

Braille is an exceptional solution devised by a young blind boy, offering everyone the independent ability to read and write. I find myself wondering, “What would Louis Braille have done to counteract today’s decline in braille education and literacy?” Something remarkable, no doubt.

Click to learn more about braille illiteracy and/or to help.

Link to J.K. Rowling’s Harvard University speech.

Back- Click to return to the J.K. Rowling Braille Book.